9th September 1513

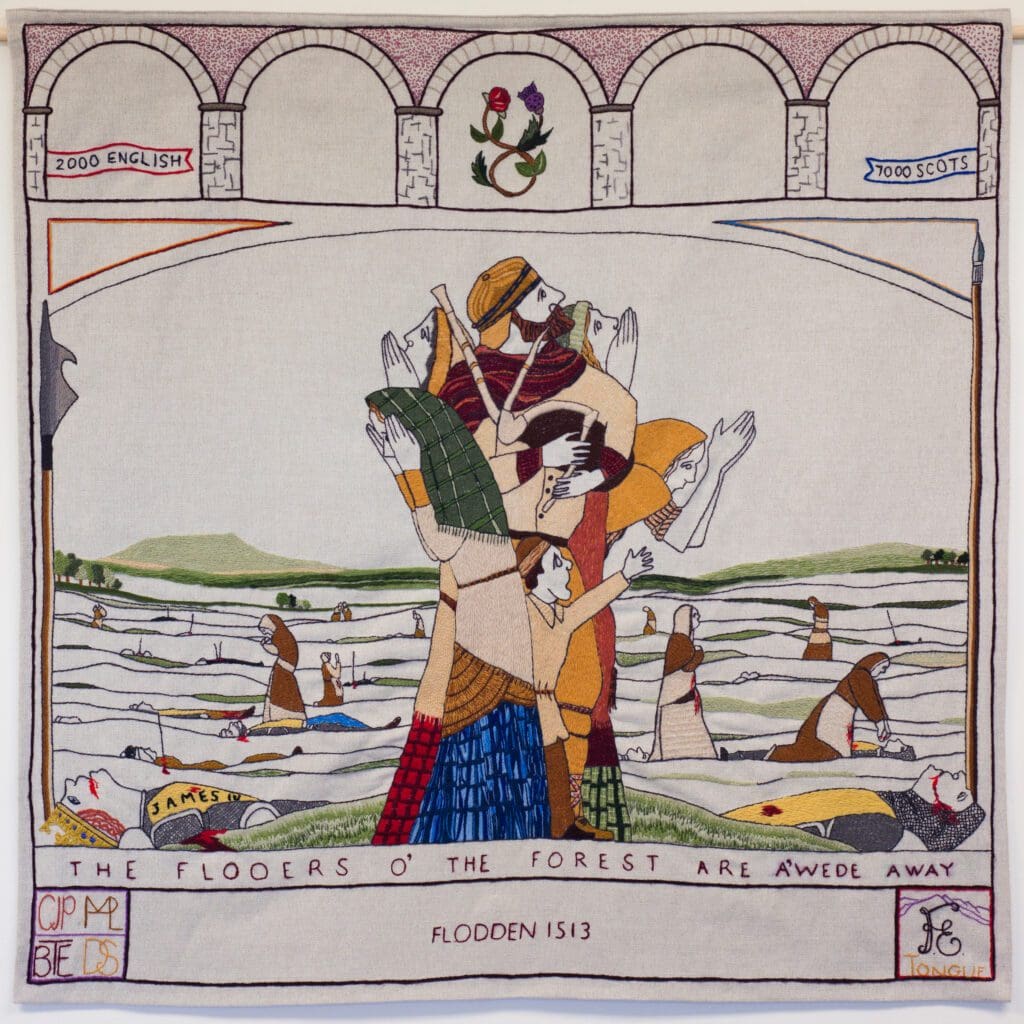

Panel 40 of the Great Tapestry of Scotland depicts the Battle of Flodden, described by some as the last great medieval battle in the British Isles.

The years leading up to the Battle of Flodden were marked by a series of smaller conflicts, border skirmishes, and political intrigues. English and Scottish troops clashed along their shared border, stoking animosities on both sides.

At the heart of this story were two monarchs, King Henry VIII of England and King James IV of Scotland. Henry was eager to assert his authority both domestically and internationally. James on the other hand, was a Renaissance monarch, renowned for his cultural patronage and ambitions to strengthen Scotland’s position on the world stage.

The road to Flodden began with the diplomatic dance of alliances and marriages. 10 years earlier, in 1503, King James IV of Scotland married King Henry VIII of England’s sister, Margaret Tudor, creating a significant family connection between the two monarchs. This marriage was meant to secure peace and cooperation between the neighbouring realms. However, Scotland had a longstanding alliance with France, known as the Auld Alliance, which dated back to the late 13th century. This alliance was a thorn in the side of England, as it meant that Scotland could potentially become a staging ground for French invasions.

As continental tensions escalated, Henry VIII sought to pressure James into breaking the “Auld Alliance”. Henry hoped to draw Scotland into his own orbit of influence but James, while maintaining diplomatic relations with England, remained committed to his French allies.

In 1513, the situation reached a boiling point. Henry VIII launched a military campaign into France, seeking to claim territory and glory on the continent. This move was a direct challenge to the Auld Alliance, and James felt compelled to honour his obligations to the French.

In keeping with his understanding of the medieval code of chivalry, King James sent notice to the English, one month in advance, of his intent to invade. This gave the English time to gather an army. After a muster on the Burgh Muir of Edinburgh, the Scottish army moved to Ellemford, to the north of Duns in the Scottish Borders, and camped to wait for the Earl of Angus and Lord Home. The Scottish army then crossed the River Tweed into England near Coldstream.

Panel 40 was stitched in Tongue, by Helen De La Mar, Caroline Proctor, Diane Skene and Belinda Trustram Eve.

Henry was in France with the Emperor Maximilian of the Holy Roman Empire at the siege of Thérouanne at the time so his wife, Catherine of Aragon was regent in England. However, Henry had already organised an army and artillery in the north of England to counter the expected invasion. A year earlier, Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, had been appointed Lieutenant-General of the army of the north and was issued with banners of the Cross of St George and the Red Dragon of Wales.

The Scottish Army that stood on Flodden Field on the 9th September 1513 was the biggest ever raised in Scotland at the time with estimates ranging from 35,000 – 60,000 men. Commanded by King James IV of Scotland and split into 4 divisions, the Scottish army were mainly equipped with 18 foot long pike supplied to them by their French allies. This new weapon had been used with devastating effectiveness on the Continent but it required discipline, training and suitable terrain to be effective. The kings secretary, Partick Paniter, held command of the Scottish artillery which consisted of mainly heavy siege guns including the” Seven Sisters” – five great curtals and two great culverins. These modern artillery pieces could fire a 30kg ball some 1800 meter, but heaviest of these required a team of 36 oxen to move each one and were only able to fire once every twenty minutes at the most.

Opposite them Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey stood in command of the English army. Numbering some 26,000, the English army was armed mainly with bills, a more traditional polearm, with a large contingent of archers armed with the English Longbow. The English artillery consisted of significantly smaller, light field guns. Despite being smaller than their Scottish counterparts they were more easily handled and capable of more rapid fire. Behind the ranks of English soldiers stood a contingent of mounted Borderers, held in reserve and commanded by Thomas Dacre, 2nd Baron Dacre.

At 4 pm on the 9th September 1513 on a wet and windy field, King James IV of Scotland initiated the Battle of Flodden. His artillery opened fire, with limited success. Poor gun placement and shooting downhill hindered the Scots.

The battle unfolded as Home and Huntley’s Scottish forces advanced downhill toward the English under Edmund Howard. The Scots, heavily armoured in the front ranks, thwarted English archers. As the English were pushed back, Dacre’s light horsemen intervened, leading to a stalemate.

King James observed this and ordered the next Scottish division led by Errol, Crawford, and Montrose to advance. They encountered marshy ground worsened by rain, disrupting their pike formations. Scots dropped their pikes and resorted to swords and axes. Close-quarter combat favoured the English with bills.

Witnessing these difficulties, King James charged forward, placing himself in personal danger. He reached Surrey’s bodyguard but made no further progress. The Highlanders of Argyll and Lennox’s formation held back.

Stanley’s English force arrived on the right of the Scottish line, launching arrows into the vulnerable Highlanders. Fierce fighting continued as English formations overcame Scottish forces. An order not to take prisoners resulted in high Scottish nobility casualties. King James, with two arrow wounds and bladed weapon injuries, was found among his fallen bodyguard. He was the last British monarch to die in battle. Home, Huntly, and their troops were among the few to escape intact, while others scattered and were pursued by the English.

The bill verus the pike

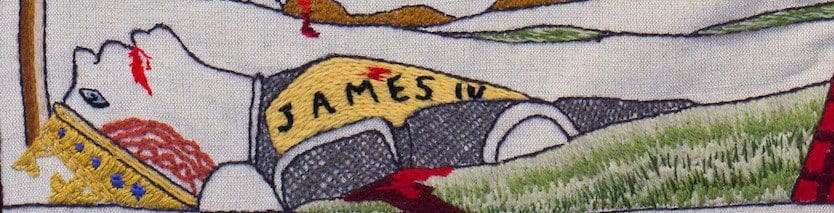

James IV’s death on this rainy field can be seen on the bottom of the panel, and continued his family’s legacy of untimely deaths. His father was killed age 33 during Battle of Sauchieburn, his grandfather at 29, when a cannon exploded beside him during the Siege of Roxburgh Castle, his granddaughter Mary, Queen of Scots, was beheaded aged 44 for plotting against her cousin Elisabeth I of England and his Great Grandson – Charles I – was executed by the English Parliament following the English Civil War.

The Stitchers Story

Panel 40 was stitched a group of 4 based in Tongue, in on the north coast of Scotland. The group found it poignant to be stitching the devastation on the battlefield, and the dead King James IV.

The Scottish thistle and English rose can be seen in the top centre of the panel, representing the English and Scottish armies during the battle.

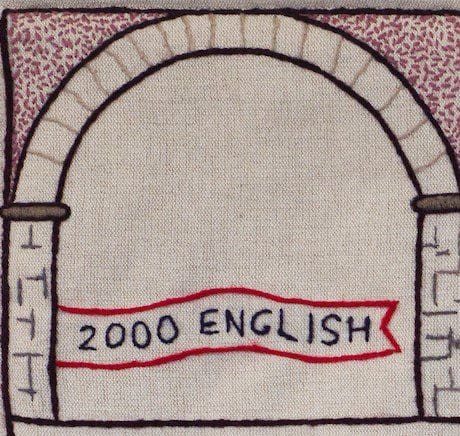

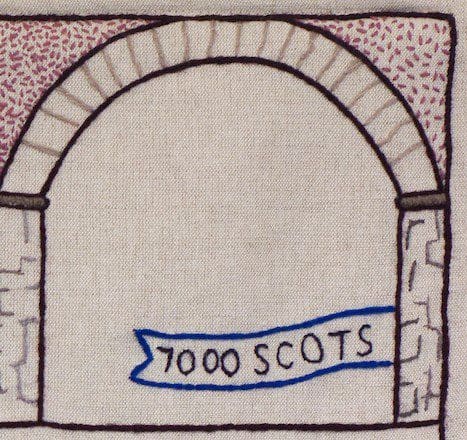

On either side of the panel are two numbers, representing the estimated number of deaths on each side.

Sharing Yarns

During the creation of the Tapestry, all the stitchers involved were encouraged to record their experiences. These diaries have been compiled into a book, telling the story of the Tapestry, by those who made it.

To find out more stories about the stitching of the Tapestry, from the stitchers themselves, pick up a copy of “Sharing Yarns” compiled by Dorie Wilkie, the Head Stitcher of the Great Tapestry of Scotland.

Have you got a specific panel you’d like to know more about? A period of history you love? Something new you’d like to discover?

Suggest what panel we dive into next:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.