23–24 June 1314

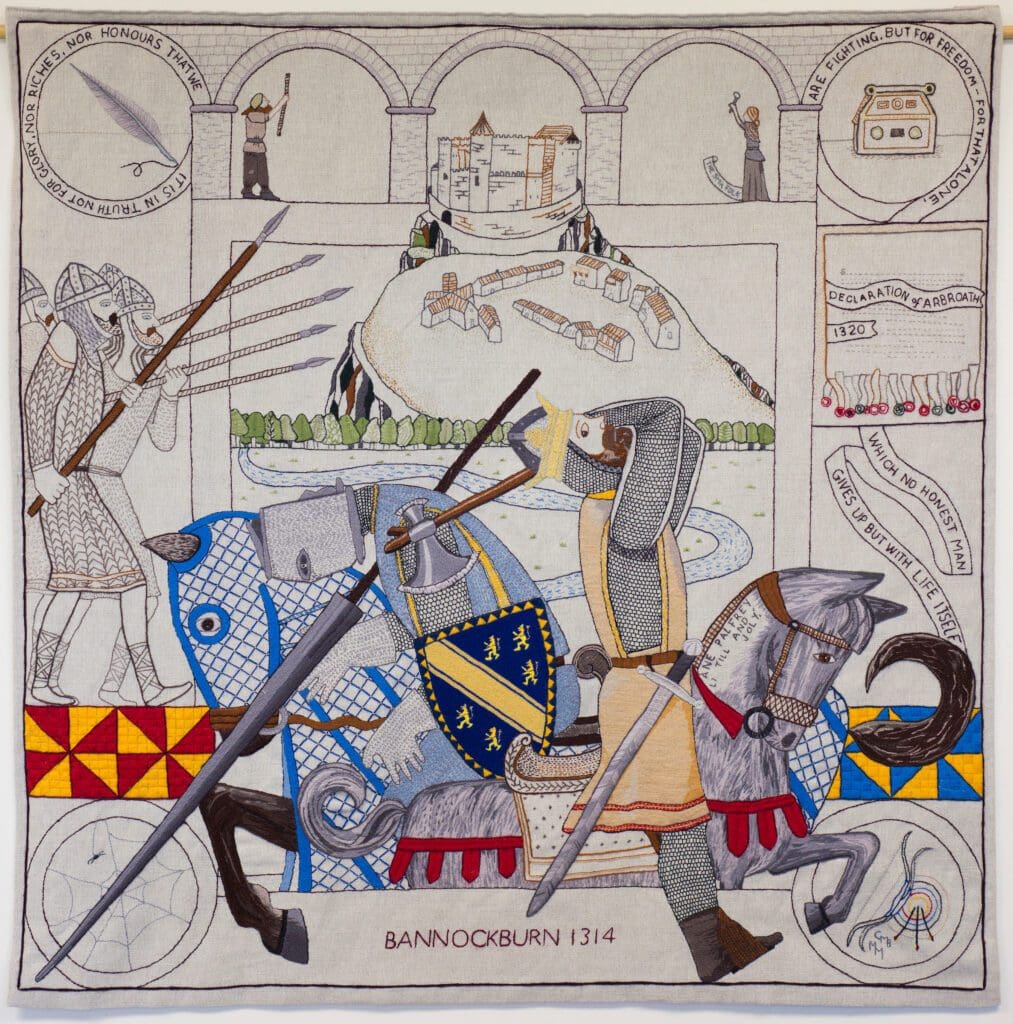

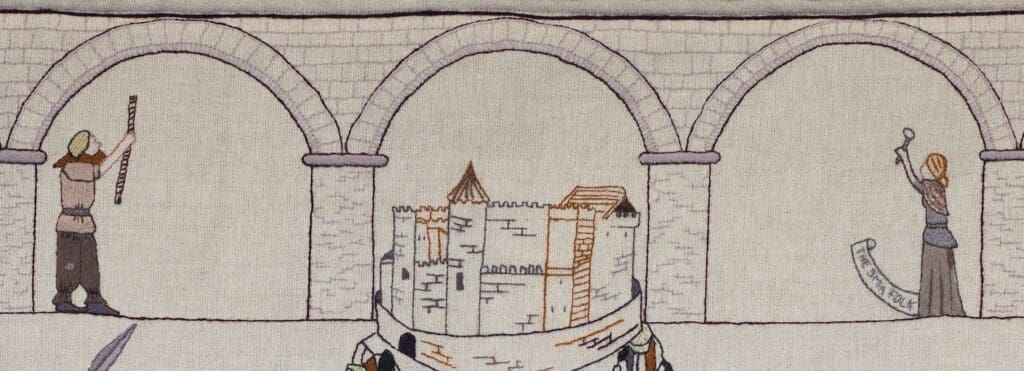

Panel 30 of the Great Tapestry of Scotland brings to life this clash between Robert the Bruce and King Edward II.

The Battle of Bannockburn, which took place in 1314, was a significant conflict in Scottish history during the First War of Scottish Independence. It marked a pivotal moment in the struggle between the forces of Scotland, led by King Robert the Bruce, and the English army, commanded by King Edward II. The battle lasted an impressive two days, in a time when most battles last hours at the most and became a turning point in Scottish history.

Robert the Bruce had strategically chosen the location, using the marshy terrain and the Bannockburn stream to his advantage. The Scottish forces, comprising mainly infantrymen, formed schiltrons — tight defensive formations armed with spears.

The English army, led by King Edward II, had both infantry and cavalry and outnumbered the Scots. However, the marshy ground and limited space made it difficult for their cavalry to charge effectively. Robert the Bruce skillfully directed his forces, using clever tactical maneuvers that exploited these challenges.

Bruce divided his army into four divisions with the first commanded by Bruce himself The second was commanded by Edward Bruce, his brother, the third by Thomas Randolf, the Earl of Moray and the fourth, commanded jointly by Sir James Douglas and the young Walter the Steward.

Given the honour at his Bruce’s side was Angus Og Macdonald, Lord of the Isles who had brought thousands of Islesmen to Bannockburn, including gallowglass warriors.

In the early stages of the battle, an English knight, Henry de Bohun, saw Robert the Bruce from across the battlefield. Fuelled by bravery, ambition, and a desire for glory, Henry saw this as an opportunity to cement his name in the annals of history.

Riding in the vanguard of heavy cavalry Bohun charged at Bruce, who, much more lightly armoured, was riding a small palfrey and armed only with an axe. Bruce turned to face him and and charged. With deft agility, the Scottish king skilfully evaded the oncoming lance, nimbly moved his horse to one side, stood up in his stirrups and hit de Bohun so hard with his axe that it cut through both Sir Henry’s helmet and skull and into his brain.

Back at the Scottish line Bruce’s generals reportedly condemned his actions as reckless. Bruce was said to be only disappointed he had broken his good axe.

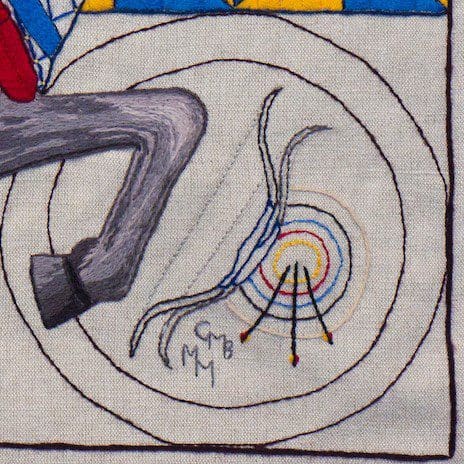

Panel 30, stitched in Falkirk and Stirling, by Caroline M Buchanan and Margaret Martin, the “Two Toxophillists”

As the battle began, the Scottish schiltrons stopped the English cavalry in their tracks, inflicting heavy losses. The Scottish infantry stood firm, repelling multiple English attacks with discipline and resilience. Bruce’s tactical mastery, combined with his troops’ determination and morale, gradually turned the tide in favor of the Scots.

Despite their efforts to regroup and launch fresh assaults, the English forces failed to break through the Scottish defenses. Frustration and confusion grew among the English ranks, resulting in disorderly retreats and chaos. The Scottish forces seized this opportunity and launched a counterattack, further demoralizing the English troops.

The Battle of Bannockburn concluded with a resounding victory for Scotland. The English suffered heavy casualties, with estimates ranging from 4,000 to 11,000 men, while the Scottish losses were minimal in comparison. This decisive Scottish triumph bolstered Robert the Bruce’s position and ultimately secured Scotland’s independence from English rule, leading to the signing of the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton in 1328.

The Battle of Bannockburn remains a crucial event in Scottish history, symbolizing the indomitable spirit and determination of the Scottish people in their fight for freedom. It solidified Robert the Bruce’s legacy as one of Scotland’s greatest heroes and marked a turning point in the country’s struggle for independence.

The Battle of Bannockburn was more than just a clash between Scottish and English forces; it was a symbol of Scotland’s unwavering fight for independence. Robert the Bruce led his army with unmatched bravery and strategic prowess, triumphing against the odds.

If you want to learn more about the Story of Scotland, make sure to explore all 160 panels of the Great Tapestry of Scotland.

The Stitchers Story

Panel 30 was stitched by two friends. Owing to their love of Archery they quickly decided that their group name would be “The Two Toxophilists”. Following a visit to see the Prestonpans Tapestry, Margaret and Caroline were inspired to volunteer to work on the Great Tapestry of Scotland.

They sat together on 2nd September 2012 and simultaneously made the first stitch.

They would meet two or three times a week, some days really focusing on stitching, some days planning how to tackle specific areas. With books of stitches and notes all around them, they did a huge amount of work together. They worked simultaneously on large sections and this project became a very shared experience. Later they would move it between them, travelling from Falkirk and Stirling every two weeks but Caroline and Margaret would still meet up twice a week to work on it together.

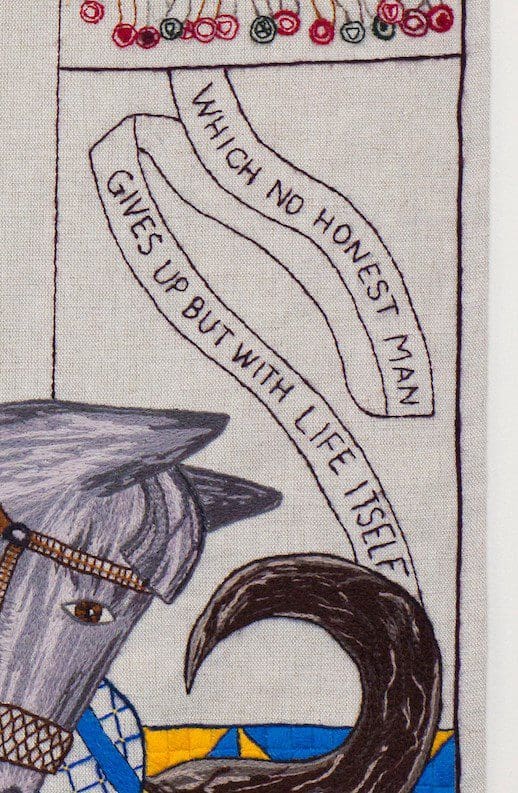

Often some areas were stitched, undone and restitched but the largest area to be radically changed was Henry de Bohun’s shield. Margaret has spent many hours stitching this but it was changed to better represent the coat of arms of the de Bohan family. The decision to change this was made fairly close to the deadline and although the finished result was fantastic Margaret’s nerves (and fingers!) may have suffered.

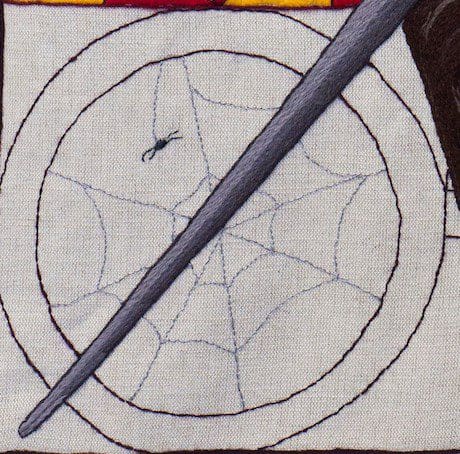

Sma’ folk and Spiders

Although the accuracy behind the stories of Bruce’s spider and the sma’ folk are questionable, these two iconic elements of the story of Bruce and Bannockburn have earned a well deserve place in the Panel

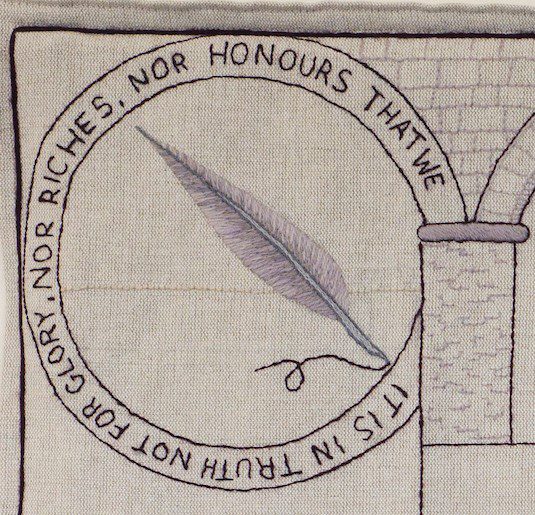

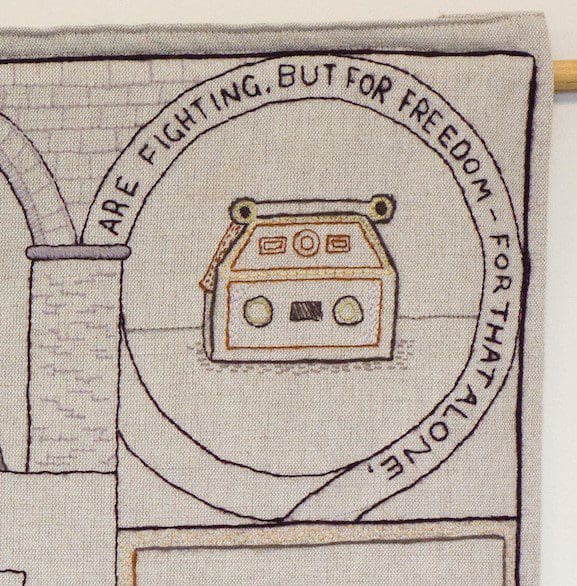

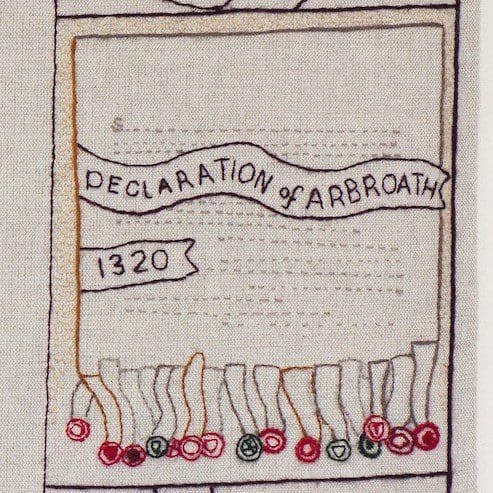

Also featured within the panel are references to the Declaration of Arbroath. Written in 1320, The Declaration of Arbroath is widely considered as one of Scotland’s most iconic documents. Signed by eight earls and 31 barons of Scotland, the letter was sent to Pope John XXII as an appeal, designed to persuade the Pope to reconsider his approach to the long-running Anglo-Scottish conflict.

Most probably drawn up by the Abbot of Arbroath, the document would have been authenticated by around 50 seals, although only 19 now remain.

It is perhaps now, most famously known for the quote:

"As long as a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be subjected to the lordship of the English. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself"

Sharing Yarns

During the creation of the Tapestry, all the stitchers involved were encouraged to record their experiences. These diaries have been compiled into a book, telling the story of the Tapestry, by those who made it.

To find out more stories about the stitching of the Tapestry, from the stitchers themselves, pick up a copy of “Sharing Yarns” compiled by Dorie Wilkie, the Head Stitcher of the Great Tapestry of Scotland.